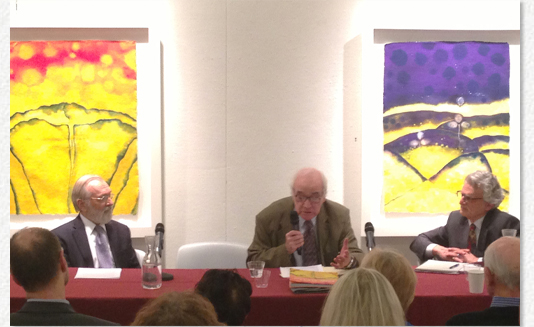

THE ART OF BASIL ALKAZZI

Donald KUSPIT, Matthew BAIGELL, Michael ROYCE, Judith BRODSKY,

Harry NAAR at Rider University

FEBRUARY 20,2014

MATTHEW BAIGELL: We can all agree that Basil Alkazzi is a spiritual person and certainly a spiritual artist. Donald Kuspit, in his writings has noted that Alkazzi finds the life-force in, say, flowers that can be transformed into spiritual entities, meaning that "natural life is simultaneously spiritual life" and as such is a sign of the spiritual purpose and sacred character of the cosmos. As Alkazzi has stated "The perfection of spirituality is sought where the spirit body lives in total harmony with the universal spiritual entity of timeless moments". In short, Basil Alkazzi seeks to be one with the universe, to be part of what we can call the "Mystical Stream".

To understand Basil Alkazzi's art better, I want to compare some of his works to those of a few American artists and to make the point that there is no single spiritual style or single spiritual view of the world. Each of us, if so inclined, finds his or her way, or rather searches for his or her way, to that mystical stream, which some people may call a "puddle of water".

Basil does it, as this exhibition indicates, through landscape forms. As he has indicated he's spent a lot of time gazing at the sky, sunrises, clouds, and in general the way shifting light affects everything that we see on land and water. I don't mean merely looking at objects as if passing by, but in effect devouring them visually.

This painting is by John Kensett, mid-19th century American artist. It is much more meditative, and to the reflections of the sky and water Kensett wants to suggest continuity, I believe, between physical matter- between the water and a sense of spiritual immanence in the sky. This is certainly one aspect of spirituality, or as Alkazzi has said: "Nothing lives forever on a plane, and nothing dies- there is only a passing on from one form to another, from one sphere to another". In this painting, from the physicality of water to open space, from the earth to the heavens. That is, there is a unity binding all things together. So Alkazzi is not concerned solely with painting an inner vision, but rather with the connectedness of earth and heaven, the here and there.

This painting is by John Kensett, mid-19th century American artist. It is much more meditative, and to the reflections of the sky and water Kensett wants to suggest continuity, I believe, between physical matter- between the water and a sense of spiritual immanence in the sky. This is certainly one aspect of spirituality, or as Alkazzi has said: "Nothing lives forever on a plane, and nothing dies- there is only a passing on from one form to another, from one sphere to another". In this painting, from the physicality of water to open space, from the earth to the heavens. That is, there is a unity binding all things together. So Alkazzi is not concerned solely with painting an inner vision, but rather with the connectedness of earth and heaven, the here and there.

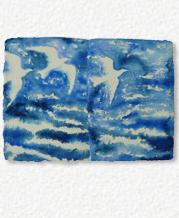

In this comparison, a bird in flight becomes for Alkazzi a painting called Dream Odyssey Revisited. An Odyssey means a trip and here the birds are either over water or very high in the sky. Georgia O'Keeffe also exhibits a kind of spirituality in many of her paintings. Here we see a blackbird. Of this she said that the snow covered hills seem to hold up the sky. In effect they are attached, not separate entities.

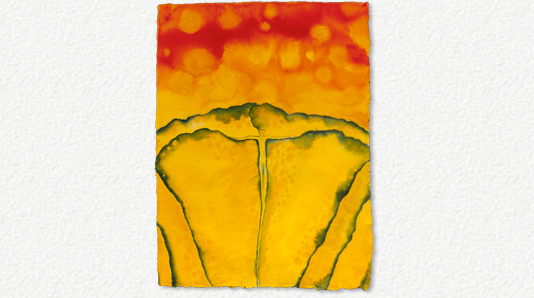

There are many flower paintings in this exhibition.

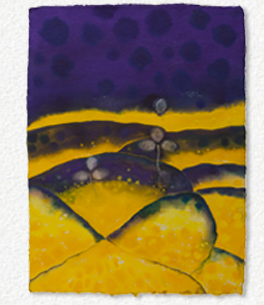

Now look at this painting called Lilium, the genus to which lilies belong. It is a Lily, and it is important to remember Alkazzi really looked at nature, what he called heaven on earth. The flower is set against a blue landscape and some of the spots on the flower seem to have drifted off into the atmosphere. Alkazzi's flower appears diaphanous,translucent. It loses its material presence, signalling that it has become one with the surrounding space. It strikes me, as a perfect illustration of Basil Alkazzi's belief "of the life-force embodied in nature, all of nature." So, this becomes a mystical dreamscape.

Now look at this painting called Lilium, the genus to which lilies belong. It is a Lily, and it is important to remember Alkazzi really looked at nature, what he called heaven on earth. The flower is set against a blue landscape and some of the spots on the flower seem to have drifted off into the atmosphere. Alkazzi's flower appears diaphanous,translucent. It loses its material presence, signalling that it has become one with the surrounding space. It strikes me, as a perfect illustration of Basil Alkazzi's belief "of the life-force embodied in nature, all of nature." So, this becomes a mystical dreamscape.

Now here are two ways to try and capture the life-force Alkazzi's Blossoming Spring. Here, it is a calm movement from one state to another. I am comparing it to Charles Burchfield's Springtime in March, a much more frenzied way of showing the forces of nature. Burchfield said of works like this that it was his task "to recreate and re-experience the rhapsodic impression of life and Nature." And "creatures and plants seem to be intoxicated by the sheer ecstasy of existence on such a day as this."

Alkazzi would have agreed with Burchfield's statement that he, Burchfield, when working from Nature was really painting from memory trying to recapture the first impression as well as the distillation of all previous similar impressions of Nature. My point here is that their intentions were similar, both trying, as Alkazzi said, to access the Life-Force embodied in Nature, but their results were different. So, there is no single spiritual style, or path to find the connections between Spirit and Substance.

How can an artist visualize the Life-Force? Here is one possible answer.

In several of Basil Alkazzi's paintings, we see what look like life-lines, veins, arteries, or as Basil said, "a visual image of a thought", the thought here being the life process itself. The obvious corollary would be the veins of the leaves. Again as Alkazzi has said, he looks a lot at nature and therefore he might have seen plants similar to this one, finding in the veins of the leaves a symbol of the life-force in all things.

In several of Basil Alkazzi's paintings, we see what look like life-lines, veins, arteries, or as Basil said, "a visual image of a thought", the thought here being the life process itself. The obvious corollary would be the veins of the leaves. Again as Alkazzi has said, he looks a lot at nature and therefore he might have seen plants similar to this one, finding in the veins of the leaves a symbol of the life-force in all things.

Another way to visualize the life-force is through flowing water, perhaps symbolic of the mystical stream or the voyage of life through time. On the left and centre are O'Keeffe's view of a river.

O'Keeffe made a few paintings of air views and roadways. And Alkazzi made this one entitled: Ascending Angel. It is as if its yellow form, signifying life, were a lifeline to someplace else, the difference being that O'Keeffe is glorifying the visible essence of the scene whereas Alkazzi is visualizing a thought.

O'Keeffe made a few paintings of air views and roadways. And Alkazzi made this one entitled: Ascending Angel. It is as if its yellow form, signifying life, were a lifeline to someplace else, the difference being that O'Keeffe is glorifying the visible essence of the scene whereas Alkazzi is visualizing a thought.

That same kind of line inhabits O'Keeffe's Black Place paintings of the mid 1940s.

The artist, Marsden Hartley explained it best when he wrote in another context that she sought a higher relation known and spoken my mystics, that that line can become a corridor of fire through which the spirit must pass in order to escape imprisonment in a world of fixed limitations. But at the same time, earthly restraints prevent one from bursting through the corridors of fire to reach the mystical stream.

The artist, Marsden Hartley explained it best when he wrote in another context that she sought a higher relation known and spoken my mystics, that that line can become a corridor of fire through which the spirit must pass in order to escape imprisonment in a world of fixed limitations. But at the same time, earthly restraints prevent one from bursting through the corridors of fire to reach the mystical stream.

As O'Keeffe said, no matter how far she walked she could never get into those dark hills. But that is what makes a spiritual journey so necessary and so maddening for those so inclined.

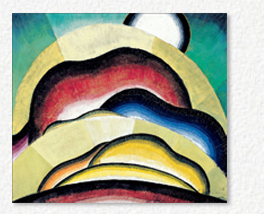

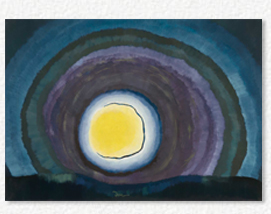

Let me end on a more positive note with these two works: Arthur Dove was a student of Theosophy, a movement, if I can reduce it to a single sentence is a movement that seeks the unity in all things. His sunrise of 1924 ascending ever upward, unifies earth and heaven. Some if the arcs seem purposely to appear as tree rings as if we were witnessing nature's inner structure. So the entire universe is a continuous medium of energy.

Basil Alkazzi's Ascension in Beatitude translates as ascension in a state of Bliss. And you can see in the centre, the tiny human body, as if it symbolizes the core of nature's unity. This would seem to be Alkazzi's ideal state of being, a combination of the natural and the spiritual evolving together in harmony. Will the human ever emerge as part of the flower? Will the Soul, can the Soul, of the universe and the human soul ever join? That, seems to be Basil Alkazzi's quest as well as the quest of the other likeminded spiritual seekers. For them, it has always been a Sacred Quest.

DONALD KUSPIT: I have known Basil a long time and I want to give you at least four reasons why you should pay attention to his art.

I always think of art as a two way relationship- the receiver is as important as the artist. You have to know what to expect from art, and what you want from art, and I'm trying to suggest why you should respect this art and what you can get from it. I also want to put it in an art history - a perspective of both contemporary and traditional modernist.

I use the word spiritual, but I don't like the word "spiritual"- It is a relatively empty signifier in English. I prefer the German word "geist" which is where this comes from. I think of Hegel and the phenomenology of the spirit or the mind, and Kandinsky on the spiritual in art. The basic German meaning of spiritual has to do with consciousness.

With Hegel you are talking about the development of consciousness as you go through the phenomenology. It's been interpreted in a variety of ways but it is basically the dialect of the development of consciousness, with religious consciousness becoming the highest consciousness, having nothing to do with any particular religion.

I tend to think of Kandinsky picking up on Hegel, pointing out that sensation can be spiritual. Hegel starts with sensation and ends with pure spirit, so-called geist, and Kandinsky is saying, complete the circle. Physical sensation itself can be spiritual. And that goes back to something Hegel says in the first part of the phenomenology. There is always a moment of negation, whenever I say "this is blue" I am also saying "it's not red". And a good artist would somehow make you know that blue is not red, maybe by bringing a little red there. So, there's always this contradiction built into it, that is the first thing I want to say.

Second, the conventional, classical meaning of mysticism, is basically the union of the self and the other, a breaking down of boundaries between the self and the other, and the transformative effect this, called an oceanic experience. Freud, famously, in the future of an illusion which dealt with religion, pointing out its many contradictions, even absurdity, as he said, argued that it's a regression to the womb. It is basically feeling blissful in the mother's womb, at one with the womb.

There is a certain concordance here with Basil Alkazzi who is dealing with Mother Nature. Nature is the mother of us all, so the mother is there. The mystical moment is the relation of the infant and the mother, just to put that in perspective and bring it down to earth.

I am also very fond of a term of another psychoanalyst, Winnicott, and what he called an ego orgasm. What he was talking about was a eureka moment of consciousness. When Archimedes saw the water being displaced he realized what it was all about, a moment of new consciousness.

Let me begin in an art historical way. Robert Motherwell, prominent expressionist painter, said very famously that the big format in one blow changed the century- long tendency of the French to domesticate modern painting to make it intimate. Of course he was in America, bigger is better.

In my opinion the loss of intimacy in art is tragic. It's been going on since Conceptualism, since Earth Art, since Pop Art. I think this contributes to the so- called dehumanizing tendencies, to refer to Ortega y Gasset.

Also, there's the corollary sense that everything is really a simulation, meaning simply, things aren't what they seem to be, it is all make believe.

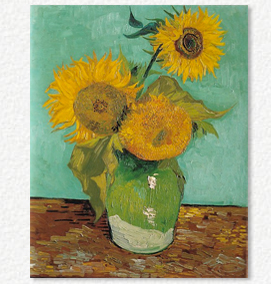

Basil Alkazzi's flowers are more libidinously, even ecstatically, alive, while Van Gogh's flowers are contaminated by the death instinct. The point is made clear by Picasso who said what counts in Van Gogh is his torment. Same thing in Cezanne, his anxiety, so the rest of it didn't matter.

A very famous psychoanalyst, Ronald Fairbairn, one of the founders of British object relational theory, a great revolutionary in psychoanalytical theory, has analyzed Van Gogh's paintings and he speaks of their sadistic character- that's a sign of anxiety.

I would say Alkazzi's paintings are reparative, he deals with flowers at work rather than bathe and dissect them in anxiety. There is no tragic torment in them, but rather joyous enlightenment emanates from them. They are life-giving, they are children of the unclouded sun, rather than insidiously morbid as I think Van Gogh's sunflowers are.

The second reason I think these paintings are worth attending to: he is a master of colour. Radiant and intense, they inform and emanate from his flowers, from his ocean. There's a strong radiant orange yellow at noon. Everything is full of light, it is a bright day, maybe a little dusk, but it is extraordinarily luminous.

It is important to note that he lives on the Mediterranean. This is a natural environment for him, where snow does not exist. It is wonderfully unclouded, he lives in Monaco where its stupendously beautiful, and his works are beautiful.

At the same time there is an abstract aspect to his works. I think one can regard them as an idiosyncratic colour field painting. The meaning of abstraction as described by philosopher Alfred North Whitehead is the process of emphasis, and emphasis vivifies life.

He also said it's a stripping bare in order to intensify feeling, and feeling for him had double significance on subjective form and the apprehension of an object- and I think that is what you have in Basil Alkazzi's work.

Next thing to notice is his painting of flowers, he restores them to "supernatural significance." The flower has a very long history of symbolic and spiritual significance. For example, St. John of the Cross regarded flowers as images of the virtues of a soul. Novalis, the great romantic painter, thought they were symbols of love and harmony characteristic of nature and indicative of the state of innocence in paradise.

The flower is the elixir of life, and I can go on and on about the life-giving spiritual significance of flowers in various cultures.

More broadly, flowers have been understood to represent archetypal figures and I think he is trying to get to the archetype of a flower in the Jungian sense. The precise meaning of the flower generally is understood by their color, their psychic significance. Thus yellow means solar, red is sanguine, blue is dream life, and the shades of psychic meaning are endless. Alkazzi's colour conveys all these psychic nuances. They tend to work on the bright spectrum, rather than the dark spectrum.

I find this very refreshing in the contemporary art world, where Andreas Serrano's photographs and Paul McCarthy's "Complex Shit", as he calls it, are celebrated. Shit has been very trendy in contemporary art since Alfred Jarry's "Ubo Roi" It's become museum art. I think it's passe, and I think flowers are not passe.

So we are moving from the profane, which has dominated modern art, to a return to the sacred.

Finally, the last thing to talk about spiritual experience: There is in England a group of psychologists doing some very important work on so-called spiritual psychology, and I want to quote from an essay well-known in the UK, by a psychologist named David Lucoff, in his essay, "Visionary Spiritual Experience"- He says it satisfies a need to transcend the limiting boundaries of the self. This has been postulated and researched as a basic neurological need of all living things. It does not mean you're going to God, it just means you are getting beyond yourself. Eric Fromm defines it as narcissism. More particularly what Lucoff says, for living human beings, efforts to break out of the standard ego-bounded entity and, one might add every day social identity. I would argue that Basil Alkazzi's visionary art convinces us that it's possible to do so and I think that is a very important use of art. It is actually a rather traditional use of art. Traditional religious art had that operational and tried to do it in different means. Basil is using more modernist means, figurative iconography of the past, and yet the flower recurs, and there is a long tradition of that.

HARRY NAAR: It seems to me in looking at this work the feeling I get from the audience and my students is that the work is uplifting, this uplifting notion of the world. I agree with Donald Kuspit, that the art world has been dealing more with torment and struggle and less so with the celebration of the beautiful and the peaceful, and the richness.

When we look at the early 20th century art those words were condemned words. So how does an artist continue to look at the world in a positive light and to create images that want to bring forth this positive feeling.

DONALD KUSPIT: I would say a key word is, look at the world. If you take a very broad history of ideas, art always served religion or the state or a combination. When these mega narratives were debunked and we were over-lightened by them- French theory is about that--- and so you have Barque analysing pool games, saying they are just as relevant.

Hegel famously said after Romanticism all art is going to be interesting. But when you don't serve God or you don't serve the State, you fall back on the self. You hear again and again, Modern artists talking about the self. Self-expression- I am this. We find the climax with Jackson Pollock, supposedly speaking out of the unconscious. Like Van Gogh he is a tormented figure. It is very interesting that you have films made about Van Gogh, Jackson Pollock, short on happy lives-- the cliche of the modern mad artist!

The problem with the self is you run out of "self' after a while. It is limited, there are conflicts with the self, etc. There's a very famous letter from Albers to Harold Rosenberg, into the modern existentialist anxiety, "Kierkegaard, we are falling through the abyss, and we are!" There are limits to that, and there is also the life force, as Freud said. Eros, not in a sexual sense, but a force that binds- also related to the external. So, what I see is Basil Alkazzi doing, is looking outside himself. No doubt his self is vested in this, but you can see things that are not himself, but, just self-expressions.

So, those are seagulls, it's like the sea. We can recognise there is some representational dimension. Something has been looked at, seen, studied very carefully, maybe in a very special state of mind. It is that kind of heightened state of consciousness. I would say that's the next way to go. There are other artists doing that, he is not the only one. Looking outside, bringing together all their stylistic knowledge, their craft, their talent, to present the external in some kind of visionary way.

One of the things that psychoanalysts always speak about is that art is the one realm where subject and object can come together. The question is what the balance is. In a lot of Modernism, there's been a balance towards the subjective.We are very interested in Van Gogh's life. I personally think that Van Gogh would not have had the reputation he has without his letters. I actually think a more innovative person was Gaugin. And then, you have a fascination with Edgar Allan Poe, and morbidity becomes "in". And then you have Picasso in the 1930s, against beauty. Barnett Newman said the point of Modern art is to destroy beauty.

Albers said anxiety is over, and just tried to deal with colour manipulations. He still had a notion of the sublime in the homage to the square. The answer is: Get beyond yourself! Beyond your suffering! -Let Art do something else for you. Sol Lewitt's idea that the work can be too beautifully done- Get over that! Try to do it as well as you can-- I feel that's where Basil is going- has gone. I think he is signalling something I see happening in other artists.

MATTHEW BAIGELL: If you look at Jackson Pollock, or whomever you want, it’s either about the self, his own life, or artists will do something about manipulation of forms which have nothing to do with anyone’s life. Then in Post Modernism there is irony, dissembling, whatever manipulation, without worrying about the viewer. Now, if you want to put Alkazzi's work into some kind of Post-Post-Modernism context, he is dealing with something authentic, in his own being, and he wants to communicate that with the viewer, and that, to me, is rare. It is not something I read about in art magazines. So, Basil Alkazzi is not Post-Modern to me, he is Post-PostModern, and also, he goes back to some notion of spirituality.

Alkazzi's art is also post-secular art - not in the sense of being religious but insinuating a Spiritual quality. The important thing is, he's trying to tell me something, not just manipulating a bunch of forms or revealing his own psyche.

I find these works very current, very Post-Post-Modern because they want to tell me something about how he feels, about the universe. He wants to communicate his authentic feelings.

DONALD KUSPIT: The terms Modern, Post-Modern- we are in a very peculiar Situation now, the old is dying, but not yet fully dead! And the new is not yet fully formed. Harold Rosenberg said the tradition of the new is here. Well, right now, all the traditions are there. There is no tradition that is special- All the art cards are on the table.

What I like about Basil is, he narrows in on a few resources. It is not modern, it is not traditional, its not Post-Modern- those terms have almost become meaningless. He has moved away from big show biz spectacle art, and is narrowing in on something very particular. You can see things connected to Kandinsky, to early Modernism, and to certain American Modernists.

HARRY NAAR: In my education, when I was coming into the development of my work, Giacometti was a big choice. Existentialism was a big voice. The beautiful and colourful paintings of Matisse were condemned-

DONALD KUSPIT: When the Museum of Modern Art had a big Matisse exhibition, I remember talking to some art critics and they hated the show. They said it gives too much pleasure! That is a sick response. You can talk about Cezanne's doubt, but you can also talk about his response to Nature, which has certain elements that are positive. It became very fashionable to suffer.

It's become fashionable to be crude, to make Outside Art, to be an outcast. There is more to life than anxiety and I think Cezanne is passe. He has a place in history, but he is one of many. In my book "The End of Art" there is a chapter about the unconscious running out of steam. Suffering has been done, its been exploited, but there is something else out there, and the problem with existentialism is it's about failure.

MATTHEW BAIGELL: Students used to ask, where does this painting come from? Ewell, this one came from Caravaggio, and this one comes from Titian. The point is, what are the transformations, not what are the influences

In medieval Renaissance, if you worked in an atelier, you did what the master said. Now, you can go to museums, read books on art, you have the whole world at your disposal. So it is not who influenced you, but who you allowed to influence you, which means you have to know something about yourself, and not just run with the herd.

With Basil Alkazzi, he is not running with any herd, he is finding what's important to him, and for himself. O'Keeffe and Dove after similar transcendence.

JUDITH K. BRODSKY: I have been living with this work for over a year, and I am immersed in Basil's world. I am immersed in the colour, I am immersed in the depth, of the images and the flowers where you feel you are being sucked into the Essence that he is portraying. I find that they overtake me. I use the word transcendent in relation to them. I think they are about certain kinds of metaphysical things. The fact that they are as intimate and make you feel you are part of the universe, and for me, that is the very essence of these particular paintings.

I am very responsive to what Matthew and Donald said about Basil transforming whatever influence and experience he has had as an artist. It seems to me that ultimately, that's what someone has to do. To transform what one knows, and what one has experienced, into something greater than the self itself, as Basil Alkazzi continues to do.

MICHAEL ROYCE: When I entered New York Foundation for the Arts in 2006 is when I met Basil Alkazzi. Through the years he has been one of my mentors, in that I believe there are, in this life, angels who come along in the form of humans and help guide us. Basil has been that for me. This man is not only a gifted individual, but he is the representation of love, not only in his work but in his conversations, his warmth and his philanthropy and the way he lives. He has taught me that no matter what we do, no matter what we strive for, if we are not doing it through the essence of love, then it isn't worth doing at all. That is a gift I will carry with me throughout my life.

A slightly edited shortened version

Matthew Baigell is a leading American art historian, and a Distinguished Professor Emeritus, Rutgers University.

Donald Kuspit is one of the most eminent art critics in the United States. He is Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Art History and Philosophy at Stony Brook University, The State University of New York.

Harry I. Naar is Professor of Studio Art and Art History and Director of the Rider University Gallery. The Rider University Art Gallery is considered by many to be one of the most important exhibition spaces in New Jersey, Pennsylvania and New York.

Judith K. Brodsky, Distinguished Professor Emerita, Rutgers University; Founding Director of the Brodsky Center for Innovative Editions at Rutgers and co-founder of the Rutgers University Institute for Women and Art.

Micheae Royce is a long time director of the New York Foundation for the Arts.